Text Outlines

Action héroïque d'une Française, ou la France sauvée par les Femmes, (Heroic action by a French woman or France saved by Women) addresses women, lamenting their inability to participate in events, suggesting instead that they should lead the way in altruism and serve the state by contributing their jewellery to its cause.

Adresse au don Quichote du Nord (An Address to the Don Quixote of the North) was attached to another pamphlet La Fierté de l'innocence. De Gouges is very exercised by both internal and external affairs, concerned that foreign influences are undermining French politics. Prussian advances had threatened the capital and although the enemy troops were defeated on 20 September at Valmy they did not finally retreat from French soil until the end of the month. This text which attempts to persuade Frederick–William II of Prussia to cease interfering in France's affairs and to return home is a response to his invasion. Throughout the text de Gouges uses the familiar first person singular 'tu' when addressing her royal addressee; despite her best efforts to prove her republican sympathies and her ability to talk plainly to royalty she was still accused of being a monarchist, something that would endanger her life.

Les Aristocrates et les Démocrates, ou le Curieux du Champ de Mars (The Aristocrats and the Democrats or the Curiousness of the Champ de Mars) this short satirical play, probably written in the second half of 1790, is set during the festival of July of that year which celebrated the first anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. It humorously portrays individuals responding to the political changes that have turned their society upside down. They are all affectionately drawn, often espousing views that make a nonsense of proscriptive rules. The badinage between the characters evokes a period before the Terror when people were freer to express their views without fear of retribution. It is a delightful, quasi–sociological, view of that moment in time. The author could not have known that her portrayal of the poet Poignardin's arrest for writing an imaginary attack on the king, would foreshadow her own, fatal, experience three years later.

Arrêt de mort que présente Olympe de Gouges contre Louis Capet (Decree of Death against Louis Capet, presented by Olympe de Gouges) is an overnight response to the vote taken by the Convention when a small majority carried the motion for Louis XVI's death sentence. The author patriotically agrees with the Convention – the king should go – but is against the death penalty because it is inhumane and ineffective politically.

Avis pressant à la Convention, ou Réponse à mes Calomniateurs (An Urgent Notice addressed to the Convention, or a Response to my Calumniators) responds to misogynist criticism. France is in crisis; Cassandra like the author's voice goes unheard. The Estates General are foundering in discord, she suggests they take time to calm down and set aside personal interests in order to regroup and address the vital problems afflicting France.

Bienfaisance ou la bonne mère (Charity or the Good Mother) This text was published in May 1788 and encloses a one-act play called La bienfaisance récompensée ou la Vertu couronnée that is at times described as a separate theatrical work which is confusing given it forms part of the narrative structure of Bienfaisance, ou la bonne mè`re and was probably not concieved to stand alone. The work presents an exemplary independent woman and her household; someone who manages her own affairs and who gives her time and affection as well as financial support to those less privileged than herself while also being a mother who cherishes her children. This decent, compassionate, competent woman never refers to any male figure of authority. She lives her life according to her own terms and discredits the commonly held view that such women are dependent courtesans.

Le Bonheur Primitif de l'homme, ou les rêveries patriotiques (The Primitive Felicity of Mankind, or patriotic reveries) this work is a creation myth that compares an original utopian world, it's decline, and de Gouges's own times. The egalitarian principles of the first state might return if the faults of the second could be addressed rather than magnified. Man seen working in harmony with the natural world and his kith and kin provides the template for a good life. The essay contains some of her most impassioned arguments against the misuse of power and wealth. De Gouges's critical view of religious organisations is clearly articulated; her preference for a form of nature worship over a supposed revealed truth is clear. In this six chapter long essay she offers varying solutions to contemporary ills without fearing the contradictions that she feels are inherent to such discourse. Olympe de Gouges anticipates criticism, in part due to her sex, but fiercely claims her right to offer her own views which, thanks to her limited erudition, might be more perspicacious than those of Rousseau himself. In reflecting on man's first community, de Gouges offers suggestions for improving the lot of man in 1789 – which is far from ideal – and hopes that an ordered constitutional monarchy can make France a better nation. Later on, as the situation in France changed, she was to abandon these royalist ideas in favour of a republic if it were democratically chosen by a majority of citizens.

Le Bon sens des Français (French people's common sense) a poster expressing belief in divorce as a source of equality within marriage by creating a fair system of separation, protecting the property of individual partners and securing rights of children to a safe future through the intermediary of family tribunals.

Le Bon sens français, ou l'apologie des vrais nobles, dédié aux Jacobins (French Common sense or the vindication of true Nobles, dedicated to the Jacobins) de Gouges uses this pamphlet to reply to comments elicited by her previous text Esprit français. She warns that the revolution is in danger of being mired in corruption and violence and draws attention to the pitiful gains made by women under the new regime.

Bouquet national, dédié à Henri IV, pour sa fête (National Bouquet, dedicated to Henri IV, for his Name Day) This text was added to some examples of de Gouges's play The Democrats and the Aristocrats, or the Curious of the Champ de Mars. On 14 July 1790 a massive celebration - the Fête de la Fédération - was held on the Champ de Mars in Paris to commemorate the falling of the Bastille in 1789. This peaceful and successful conclusion to the preceding revolutionary violence was assumed by most observers on the day to be a realistic long-term outcome. It was also, fortuitously, the Henri name day thus allowing de Gouges to incorporate both themes in this work, the historical Henri IV having become the symbol of a tolerant monarch able to create unity where discord had existed.

Les Comédiens démasqués, ou Madame de Gouges ruinée par la Comédie Française pour se faire jouer (The Comédiens unmasked or Madame de Gouges ruined by the Comédie Française in order to be performed) this lengthy pamphlet charts the performance history of L'Esclavage des Noirs, since 1785, and describes the tempestuous relationship between de Gouges and the Comédie Française.

Le Contre–poison, avis au citoyens de Versailles (The Antidote, advice to the citizens of Versailles) warns the citizenry against being led astray by insurrectional elements who are nothing more than aristocrats aiming to bring about the downfall of a new regime. Patience is needed to allow the new government to achieve its aims.

Correspondence de la cour. Comte moral rendu par Olympe de Gouges sur une dénonciation faite contre son civisme aux Jacobins par le sieur Bourdon (Court correspondence. A principled report by Olympe de Gouges on a denunciation made to the Jacobins, against her patriotism, by Monsieur Bourdon) on 28 October 1792 a Jacobin publicly accused Olympe de Gouges of disseminating a petition in favour of Louis XVI. The danger of such an accusation was enough to stimulate de Gouges to respond with Compte moral rendu printed, a few weeks later, to refute the charge made against her by giving examples of her political integrity. She also made public, for the first time, her brush with Marie Antoinette's household and her refusal of any royal favours.

Le Couvent, ou les Voeux forcées (The Convent, or the Forced Vows) was de Gouges's commentary on the political and philosophical movements that led to the de–sacralization of the Catholic Church in France. First performed in October 1790 the play addresses the horror of young people being forced into religious orders to suit their families wishes. It portrays both the patriarchal power of the old order and the more liberated views of a religion inspired by natural feelings.

Le Cri du sage, par une Femme (The Call of the wise one, by a Woman) responds immediately, like a modern day blog, to the momentous meeting of the Estates General of 5 May 1789 calling for the three parties to cast aside their personal interests in favour of the common good.

Départ de Monsieur Necker et de Madame de Gouges, ou les Adieux de Madame de Gouges aux Français et à M. Necker (Monsieur Necker and Madame de Gouges's departure or Madame de Gouges's farewells to the French and to M. Necker) this pamphlet made public de Gouges's decision to leave France in the hope that her play, L'Esclavage des nègres, poorly received in Paris, would fare better on the London stage. She uses Necker's departure to playfully contrast and compare their lives, commenting on Treasury affairs before moving on to attack French slave traders and colonists, to comment on newsworthy events such as the execution of Favras, to offer anecdotes relating to everyday life in Paris, and to skewer with her mordant wit those whom she felt had let her, or her nation, down. Having decided to leave Paris she found herself too attached to France's ever changing political situation to bear a lengthy absence and abandoned her journey.

Dialogue allégorique entre la France et la Vérité dédié aux états–Généraux (An Allegorical dialogue between France and Truth dedicated to the Estates General) a dramatic scene used to highlight the author's pacifist and anti–corruption message, followed by a new project to use culture to improve society. The text addresses the role of women in society and the creation of homes for those left without means of support.

Dialogue entre mon esprit, le bon sens et la raison, ou critique de mes œuvres (Dialogue Between my Wit, Common Sense and Reason, or a Critique of my Works) Written in 1788 and included in some examples of her newly published Oeuvres this piece presents the author's creative workings and literary engagement with customary humour and lack of pretension; by voicing a form of inner dialogue she addresses her critics - and perhaps her own insecurities - head on. The text hints at the social and political engagement that will appear in her works within a few months following the Assembly of the Notables in Versailles in November 1788.

Discours de l'aveugle aux Français (The Blind Man's Speech to the French) From early May 1789 when the deputies of the Estates General were presented to the king to June 27 1789 when they were officially constituted as the National Assembly every moment was marked by disagreement and tactical rivalry. In this piece, written in June just days before the creation of the National Assembly, de Gouges is once again begging the men in power to abandon their personal prejudices and unite as a group for the benefit of their country and the welfare of its citizens.

Les Droits de la femme (The Rights of woman) written in direct response to the disappointingly exclusive Rights of Man to show that equality between the sexes is essential for the health of any nation. The suggested contract between women and men that ends the piece is so ground breaking that even two centuries after its creation it continued to be problematic. It is one of the first published tracts in favour of the political rights of women.

L'Entrée de Dumouriez à Bruxelles, ou les Vivandiers (Dumouriez's Entrance in Brussels or The Sutlers) written in November 1792 and published in early 1793 this five act play celebrates the liberation of the Belgians by Dumouriez from their Austrian oppressors, the playwright seeing in that moment a perfect symbol of republican patriotism, the new French regime spreading its message of liberty and equality beyond its borders for the benefit of mankind. For a play set in the midst of a military campaign if offers robust female characters. Its creation proved difficult and its few performances disastrous. De Gouges elaborates on all of these trials and tribulations in her preface entitled Plots Unveiled. The play, written so soon after the events it portrayed, was supposed to transport an enthusiastic and patriotic audience to the heart of a current campaign, instead it was delayed to such an extent that any topicality had become virtually irrelevant. Unfortunately it is of more interest now to readers of de Gouges's works and those who study that period, than it was to audiences in 1793. Written as a pièce de circonstance it was never meant to shine by its literary merit, once its topicality removed, little could save it from critical mauling.

Épitre à sa majesté Louis XVI (Dedicatory epistle to his majesty Louis XVI) this pamphlet expresses de Gouges's frustration at Louis XVI's inactivity in supporting the creation of a constitution. One can see the author's attachment both to her king, and to the ideal of a constitutional monarchy. Opinions like these were held against de Gouges at a later date when she was accused of being a monarchist. In 1793 such charges often led to imprisonment and death; they also have posthumous implications when historians assess the political affiliations of their subjects. It is not often remembered that Marat, whose republican credentials are never in doubt, wrote in 1788, 'Blessed be the best of Kings!' stating that only the enemies of the state would wish to 'overthrow the monarchy' (quoted in Conner, Jean Paul Marat Tribune of the French Revolution, Pluto Press, 2012). Like de Gouges, and so many others, Marat feared that anarchy would ensue if the monarchy were to be overthrown; reform within the realm not revolution was still considered the better outcome.

L'Esclavage des Noirs (Black Slavery) is the revised version of Zamore et Mirza (see below). The play is tighter with fewer characters and a clearer dramatic intent. The Preface reflects de Gouges's thoughts on the violence that had erupted in the colonies in 1791 and the subsequent laws that offered some freedom to the enslaved while also creating draconian responses to the insurrection.

L'Esprit Français, ou Problème à résoudre sur le labyrinthe de divers complots (French wit, or Resolving the labyrinthine problem of the various plots) is boldly dedicated to Louis XVI, addressed to the Legislative Assembly, the Jacobins and the Feuillants attacking the pervasive, corrupting, influence of power and the disorder at the heart of the administration, the threat of civil war and the lack of common sense, or reason, used to persuade all to work for the good of France and its people rather than to seek personal reward.

Les Fantômes de l'opinion publique (The Ghosts of public opinion) the author took up her pen to support the moderate elements following the events of September 1792, terrified that insurrection could lead to both internal and external war. Action must be taken before it is too late.

La Fierté de l'Innocence; ou le Silence du véritable Patriotisme (The Pride of innocence or the Silence of true Patriotism) is one of the rare responses to the appallingly bloody massacres of September 1792, publicly exclaiming against the use of violence to uphold governmental change, attacking not only those actually responsible for the bloodshed but also those who stood aside and let it happen.

La France sauvée, ou le tyran détrôné (France saved, or the tyrant dethroned) begun in August or September 1792 this play was never finished and was found in manuscript form when de Gouges's lodgings were searched by the authorities following her arrest in June 1793. With tragic irony her accusers used the words she had given Marie–Antoinette as proof of the playwright's own political views. When de Gouges stated that the speeches she had written accurately depicted the monarch's ideas, rather than her own, she was derided. Her life ended at the guillotine: of all the characters in her play only one survived the effects of the Terror to live beyond 1793; there is something Shakespearean in the scale of such slaughter, one that would have been unimaginable to de Gouges when she put pen to paper in 1792.

Grande éclipse du Soleil Jacobiniste et de la Lune Feuillante (Great Eclipse of the Jacobin Sun and the Feuillant Moon) Jacobins and Feuillants are both attacked in equal measure for their violent, inflammatory, tendencies.

L'Homme Généreux (The Honourable Man) is a five act drama that is closely linked to de Gouges's Memoire de Madame Valmont, placing the eponymous heroine of the Memoire at the heart of the play. The 'generous man' is a nobleman whose moral conundrum and emotional development thematically drive the pedagogic message of the work. Deception, attempted rape, societal power structures, the effects of poverty and debt, love both familial and romantic, these are the situations that have to be resolved before the generous man can see clearly where his heart and duty lie. One evil character comes perilously close to destabilising all. Good triumphs over evil in the end but only after deception, both general and of the self, has been abandoned in favour of honesty and cohesion. Evil loses its power when all right minded people set aside their imposed class and gender strictures and embrace their shared humanity. Bound with other plays, it featured in the 1788 edition of de Gouges's Œuvres but was not performed on the stage.

Lettres a la Reine, aux Généreux le l'Armée, aux Amis de la Constitution et aux Françaises citoyennes (Letters to the Queen, to Army Generals, to Friends of the Constitution and to French Citizenesses) this pamphlet unites the letters written by de Gouges to various parties in which she sought, from the powers that be, support for a group of women to join a procession in honour of the murdered Mayor of Etampes. Crucially it had been framed as a celebration of the rule of law. De Gouges felt strongly that if women had to obey the law, then they must be allowed to help create that law. Participating in such an official festival was a step towards female representation in the political arena. Her address to Marie Antoinette was to have grave consequences for de Gouges a year later.

Lettre à Monseigneur le duc d'Orléans (Letter to his Lordship the duc d'Orléans) written in early July 1789 this open letter shows de Gouges reacting to the turmoil she fears the duc d'Orléans is fomenting at the Palais–Royal. Its publication managed to upset both the court at Versailles and the duc's entourage. She hoped to persuade the duc that reasoned debate and generosity were needed to steer France towards a better future, not further public disorder.

Lettre au peuple, ou Projet d'une caisse patriotique, par une Citoyenne (Letter to the people, or Patriotic purse project) establishes the author's persona: independent; untutored; a natural talent. She uses personal experiences to underpin political and philosophical arguments, bemoans the cynical manipulation of the populace to riot and expresses a horror of civil war. Voluntary taxation is suggested to redress the state's deficit. Society needs to change to reduce needless expenditure and everyone must work for the common good. The role of women in society is discussed.

Lettre aux Littérateurs français (Letter to the French Littérateurs) written in the spring of 1790 in response to the author's treatment at the hands of the Comédie–Française and her inability to persuade the authorities to act on her behalf. De Gouges hoped with this letter to influence writers and journalists to act on her behalf. The text was well received by several newspapers. Opening with the ironic trope of weak womanhood she moves on to hit hard at the men in power, both in theatre and government, who are behaving, post–revolution, with the despotism so reviled during the previous regime.

Le Mariage inattendu de Chérubin (The Unexpected marriage of Chérubin) after seeing Beaumarchais' La Folle Journée, ou le Mariage de Figaro in 1784 de Gouges was inspired to write a sequel, Les Amours de Chérubin. In her enthusiasm for the original she viewed her own work as an homage to the great playwright. He did not share her opinion, accused her of plagiarism, and used his considerable fame and influence to end any hopes of it being played. Realising that the performing life of her play was over de Gouges published it, in 1786, under the title Le Mariage inattendu de Chérubin. The storyline is similar to the original in which a young bride is threatened by an aristocratic roué who thinks he is entitled to a wedding night initiation but the narrative is altered to offer a different resolution, one that seeks to end predatory male behaviour and improve family ties in order to create a better society. The women in the play are people of integrity, strength and resolve who do not rely on intrigue to achieve their ends. De Gouges was offering the public a view of her sex that was inspirational and aspirational. The old order, as epitomised by the Count and Countess and their dysfunctional union, could (and should) be replaced by marriages founded on mutual trust and affection. Beaumarchais who, despite modern interpretations, had no interest in bringing down the old order – and certainly no interest in female emancipation – may have found this play far too progressive for his taste.

Mémoire de Madame de Valmont (The Memoir of Madame de Valmont) is a semi–autobiographical epistolary novel written in 1784 following the death of Olympe de Gouges's supposed father, Jean–Jacques Le Franc de Pompignan, the work was eventually published in 1788. It is a response to the harsh treatment the author received at the hands of her natural family, reflecting, within its fictional world, the reality of de Gouges's situation. With its multiple voices and satirical flair it creates a hall of mirrors, each reflection giving another view of the central narrative that attacks aristocratic privileges and religious bigotry. It challenges assumptions of truth and fiction, highlights the lack of faith shown by men when they make promises to women and deplores society's unwillingness to allow women to voice their concerns or take part in political debate. The eponymous heroine is seen to take charge of her life despite prejudicial attitudes towards illegitimacy; she is assisted by a female author whose own history is remarkably similar. These multiple projections of Olympe de Gouges's own situation, as artful as they are, express the frankness and courage with which she attempts to break down the constraints imposed on her, and others, by society's guardians.

Mes Voeux sont remplis, ou le Don patriotique (My Wishes are fulfilled, or the Patriotic gift) acknowledges events and projects hopes for the future.

Mirabeau aux Champs–élysées (Mirabeau in the Elysian Fields) is a one act play written in homage to the politician and performed within a fortnight of his death. Commemorative plays and the cult of great men were fashionable in the 18th century. The revolution needed to anchor its nation building in just such terms. Theoretically this play should have been a success for despite the immoderate cuts made to it by the theatrical troupe, the text splendidly represented de Gouges's personal views (closely allied to those of Mirabeau) on France becoming a constitutional monarchy while also providing her with the opportunity to showcase great women and give them salient words on the position of women in 1791. The recent freeing up of theatrical censorship created a slew of plays on contemporary subjects, most written in haste and consigned to oblivion. De Gouges was part of that trend, seeing theatre as the perfect medium to put forward her views on current affairs. The play was performed twice in Paris to full houses, with some success, and then in the provinces, most notably in Bordeaux, on June 1st. The royal family's flight to Varennes towards the end of June changed the mood of the country, audiences were no longer much interested in plays supporting any form of monarchy.

Molière chez Ninon, ou le Siècle des grands hommes (Molière visits Ninon, or the Century of great men) is a five act homage to Ninon de l'Enclos and her playwright friend. De Gouges uses the life story of the famous 17th century courtesan to create her ideal woman, someone strong, free–spirited and generous who is cherished by many friends and admirers despite living according to her own principles and not those of the society that surrounds her. The play is episodic in form and naturalistic in its treatment of its subject, indeed de Gouges prided herself on having presented the famous figures from history in her work as real people irrespective of their rank and status. The play also touches on the plight of natural children, a subject close to the author's heart, and didactically highlights the benefits of love and acceptance over the more usual rejection.

Mon dernier mot à mes chers amis (My last word to my friends) was first printed as a poster in December 1792 then bound with a previous response to Bourdon, and sent to the Convention in the same month. Discouragement following physical and verbal attacks had finally pushed de Gouges to consider leaving Paris and abandoning her writing of political tracts. This decision was swiftly overturned as, yet again, events became too momentous to be disregarded.

La Nécessité du divorce, ou le Divorce (The Necessity of Divorce, or the Divorce) was written following a debate on divorce in the National Assembly on 5 August 1790 and addresses why it is vital and the problems that may, or may not, arise from its implementation. The core arguments are put forward by an elderly bachelor but the actual marital crisis at the heart of the family is resolved by the solidarity, intelligence and courage of the two women who have been deceived by their errant husband/lover. The play highlights both contemporary attitudes regarding divorce and de Gouges's own feelings towards marriage and its indissolubility. Divorce was not legalised for a further two years: the attitudes expressed in the play were in advance of their time and, although it is one of her best plays, it found little favour and was never performed until its world premiere in 2021 by the New Perspectives Theatre Company of New York in this translation.

Olympe de Gouges au Tribunal révolutionnaire (Olympe de Gouges to the revolutionary Tribunal) accuses Robespierre of tyranny and justifies the author's own political stances.

Olympe de Gouges défenseur officieux de Louis Capet (Olympe de Gouges, Louis Capet's unofficial advocate) this letter written to the Convention on 16 December 1792 offering to defend Louis XVI was also produced as a placard liberally posted around Paris; it was disregarded and derided. In her defence of Louis XVI de Gouges expresses her customary fair–mindedness, in her understanding of the Convention's Parisian bias, her shrewdness and in her plea for exile rather than death, her pacifism. De Gouges produced three further texts in response to the negative reaction this text elicited: Mon dernier mot à mes chers amis; Addresse au don Quichotte du Nord; Arrêt de mort que présente Olympe de Gouges contre Louis Capet.

L'Ordre national ou le comte d'Artois inspiré par Mentor dédié aux États-Généraux (The National Order or the comte d'Artois inspired by Mentor, dedicated to the Estates General) In this text written shortly after the fall of the Bastille in July 1789 de Gouges expresses her own hopes and fears through the voice of a male writer in the Preface before ventriloquising Mentor to address the current political situation. De Gouges always placed humanity above social hierarchy allowing her to address anyone more powerful than herself as her equal, her own voice clear whether masked or not. Here her lifelong belief in unity and clemency is expressed against a backdrop of fear that the disunity shown by those in positions of authority might lead to a form of civil war backed by foreign powers. At this stage of the revolution she welcomed its promise of equality but feared its excessive violence and believed that a reformed monarchy was the best way forward for a safer more harmonious France.

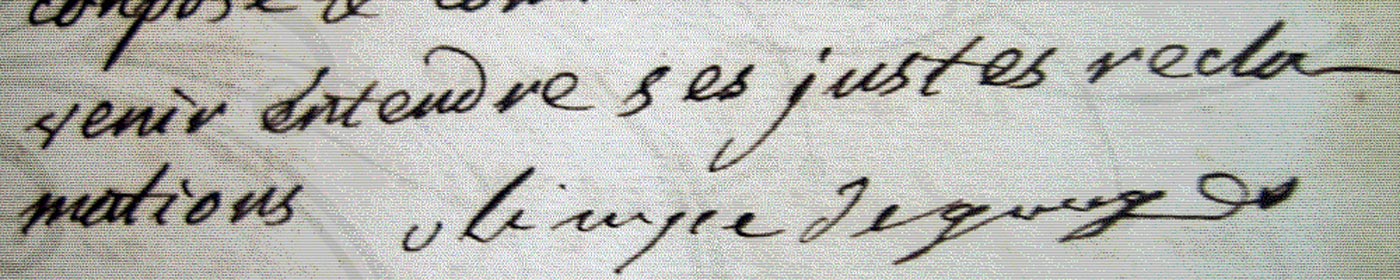

Une Patriote persécutée à la Convention nationale (To the National Convention from a persecuted woman patriot) written from prison towards the end of her life this text boldly expresses opinions with regards to her detention. The author demands to be given a fair hearing, reaffirms her fundamentally pacific republican sentiments and throws down the gauntlet to her captors.

Pour sauver la Patrie, il faut respecter les trois Ordres, c'est le seul moyen de conciliation qui nous reste (To save the Motherland the three Orders must be respected; it is the only method of conciliation that is left to us) begs the Nobility and the Third Estate to reconcile their differences to save France from her enemies, and use a ballot system to settle their differences.

Préface pour les dames, ou le Portrait des Femmes (Preface for the Ladies, or the Portrait of Women) appears in the initial volume of de Gouges's Oeuvres published in 1788. It is her first public appeal to women to mutually support each other in order that they may flourish. Trapped in a society that offers her sex few forms of genuine creative expression de Gouges warns against women using censoriousness or ridicule to belittle each other when they could be creating a sisterhood instead.

Projet sur la formation d'un Tribunal populaire et suprême en matière criminelle (Design for the creation of a supreme criminal Tribunal for the People) puts forward groundbreaking ideas for trial by jury.

Pronostic sur Maximilien Robespierre, par un animal amphibie (Prognostic of Maximilien Robespierre, by an amphibious animal) is a characteristically bold response to Louvet's accusation against Robespierre that pre–empted the latter's own response by a few hours; the indictments were only too accurate, if a year ahead of their time.

Réflexions sur les Hommes Nègres (Reflections on Negro Men) is a forceful abolitionist essay appended to de Gouges's anti–slavery play Zamore et Mirza ou l'Heureux naufrage.

Remarques patriotiques, par la citoyenne, auteur de la Lettre au Peuple (Patriotic observations, by the citizeness, author of the Letter to the People) proposes social and agrarian reform, a form of state welfare, and an equitable taxation system including wealth tax. It empathises with the poor and dispossessed, highlights the dishonesty of ministers, the wastage of needless luxury, and the damage done by those who speculate. It includes a utopian dream sequence in which the successful meeting of the Estates–General brings about great benefits for all. It addresses the King and Queen directly to pave the way for those who lack other means to make their opinions heard.

Réminiscence (Reminiscence) Published in 1788 in her three-volume edition of theatrical works this piece is sometimes referred to as a letter to the father of Chérubin i.e. the playwright Beaumarchais. De Gouges often wrote of her frustrations concerning this particular writer and of her shabby treatment by the Comédie Française over the years. In this pamphlet full of auto-biographical details she gives vent to these feelings.

Réponse a la justification de Maximilien Robespierre (Response to Maximilien Robespierre's justification) is a lightening response to Robespierre's speech of 5 November 1792 taking apart his arguments and giving full vent to the author's anger and frustration. It's pointed irony was misunderstood and taken for lunacy.

Réponse au champion Américain, ou Colon très aisé à connaître (Reply to the American Patron, or Colonist Very Easy to Recognise) This witty and courageous piece was written in January 1790 in response to an anonymous open letter - threatening de Gouges to a duel or worse - published on December 25 1789 days before the first performance of her anti-slavery play L'Esclavage des Noirs on 28 December. De Gouges had three hundred examples printed and sent to members of the Parisian governing body, the Commune. The rise of abolitionist sentiments among certain leading figures led to increased vitriol from slave traders and plantation owners who used the conservative press to attack those openly condemning them. Advised by friends to ignore the challenge, these men being ruthless and dangerous, unusually de Gouges took her time and responded in writing three weeks later.

Séance royale. Motion de monseigneur le duc d'Orléans ou les Songes Patriotiques dédiées à monseigneur le duc d'Orléans par Madame de Gouges (Royal Session. His Lordship the duc d'Orléans' Motion, or Patriotic Dreams, dedicated to His Lordship the duc d'Orléans by Madame de Gouges) was written to counter the opprobrium produced by her poster of the same name. It is a complex text, using multiple voices, which both justifies de Gouges's previous statements while aiming to conciliate those her words have offended. Her ideas are, as in previous texts, presented as dreams, or the imaginings of others, supposedly better placed to make such observations. De Gouges puts forward her suggestions for a constitutional monarchy, or a regency, and ends with her characteristic plea for improving the lot of illegitimate children.

Sera–t–il roi ou ne le sera–t–il pas? (Will he, or will he not, be King?) is a lengthy response to Louis XVI's flight arguing for a constitutional monarchy and reform of the royal household. Emigrants should be allowed to return thus bringing back their wealth to France. The duc d'Orléans is blamed for encouraging civil disorder. The text digresses to discuss the need for equitable divorce to safeguard adults and children and appears to describe the author's own financial and domestic arrangements. A National Guard made up of women is proposed to protect and guard the women of the Royal Family thus involving ordinary women in public life and diluting the influence of courtiers.

Testament politique d'Olympe de Gouges (Olympe de Gouges's Political Statement) is a prophetic pamphlet distributed to the Convention, the Commune, the Jacobins and various journalists in which the Girondins are supported and their sacrifice for a cause is celebrated.

Le Tombeau de Mirabeau (Mirabeau's Tomb) was written as an immediate response to the death of Mirabeau. De Gouges shared many of his political thoughts on France becoming a constitutional monarchy and had corresponded with him in 1789.

Les Trois Urnes, ou le Salut de la Patrie (The Three Urns, or the Welfare of the Motherland) challenges the concept of France being a Republic, one and indivisible by suggesting a democratic vote throughout the country to choose a truly representative form of government; this suggestion led directly to her execution.

Zamore et Mirza, ou l'Heureux naufrage (Zamore and Mirza, or the Fortunate Shipwreck) was written 1784, published 1788, performed 1789 with a new title L'Esclavage de Nègres, ou l'Heureux naufrage) and is the first French play to put a slave on the stage in the hero's role, to give people of colour voices equal to their white peers, to highlight the barbarity of slavery – emphasising the damage it does to both the enslaved and those who oversee the trade – while simultaneously portraying women and men as equals and addressing the problems of children born out of wedlock. De Gouges's forceful abolitionist essay Réflexions sur les Hommes Nègres was appended to this publication of the play.